The refusal by the Uganda Law Council to grant Martha Karua, a distinguished Senior Counsel from Kenya, a temporary practicing license to represent Dr. Kizza Besigye in his ongoing trial before Uganda’s General Court Martial has raised significant concerns in my mind about Uganda’s legal system, regional cooperation, and political interference. In this post, I will break down my perspective on why this decision is problematic, critiquing the reasons provided by the Law Council and exploring the broader implications it has for both Uganda and the East African Community (EAC) at large.

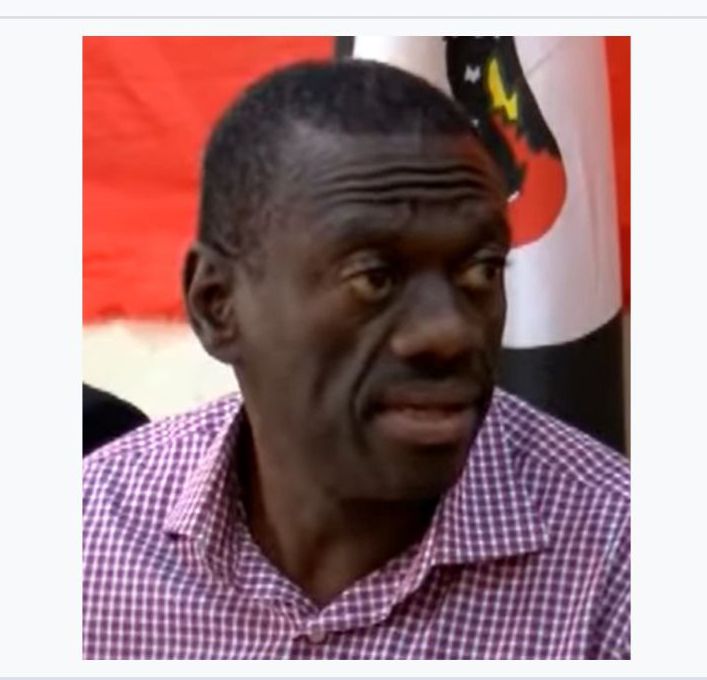

Background Context: The Case of Dr. Kizza Besigye

Dr. Kizza Besigye, one of Uganda’s leading opposition figures, was invited to Nairobi by Martha Karua for a book launch. During this event, Besigye was allegedly found with a firearm in his hotel room, which led to his controversial extradition back to Uganda. This case is more than just a legal matter; it raises important issues surrounding Kenya’s sovereignty, extradition laws, and the treatment of political figures within the region. Besigye’s trial before the General Court Martial has been heavily scrutinized, especially in light of the Supreme Court’s recent stay of a ruling by the Constitutional Court in the case of Michael Kabaziguruka v. Attorney General (Constitutional Petition No. 45 of 2016), which had declared that military courts in Uganda have no jurisdiction to try civilians.

The refusal to grant Karua a temporary license, made by the Uganda Law Council, appears to be a politically charged decision, occurring against the backdrop of these ongoing legal and political tensions. As a legal professional, I find this decision troubling, particularly when considering the broader implications for regional integration and the rule of law in Uganda.

—

The Reasons Cited by the Law Council for Denial

The Uganda Law Council gave several reasons for denying Martha Karua a temporary license to practice law in Uganda for Besigye’s defense. Let’s examine these reasons critically and reflect on the potential political undertones and legal inconsistencies involved.

1. Lack of Notarized Documents

The Law Council argued that Karua’s application was incomplete because it lacked notarized copies of her practicing certificate, a letter of good standing, nationality documents, and academic qualifications.

My View: This is a procedural issue that could have been easily remedied. Rather than outright denying the application, the Law Council could have requested the missing documents or offered Karua an opportunity to rectify the deficiencies. This decision to deny her based on minor technicalities rather than facilitating her compliance reflects poor administrative practice. A lawyer of Karua’s stature should not be obstructed by such minor procedural issues.

2. Absence of a Valid Practicing Certificate for Erias Lukwago

Another reason cited for the refusal was that Karua’s local sponsor, Erias Lukwago, did not have a valid practicing certificate. This was apparently a reason for not processing the application.

My View: The idea that Karua’s application should be rejected because Lukwago did not provide a valid practicing certificate is misguided. Upon reviewing the Judiciary website, it is clear that Erias Lukwago has an active practicing certificate for 2024. The Law Council could have simply verified this information rather than using this as a reason to deny Karua’s application. The failure to make such a simple verification indicates either an oversight or an intentional attempt to complicate the process. This was an avoidable technicality that should not have been used as grounds for denial.

3. No Special Expertise Brought by Karua

The Law Council claimed that Karua did not bring any special skills that Uganda’s legal community lacked, suggesting that her involvement in the case was unnecessary.

My View: This argument is deeply problematic. The client has a fundamental right to choose their lawyer, and Karua’s expertise was specifically sought by Dr. Besigye. Her representation was not about fulfilling some special legal need that Ugandan lawyers couldn’t address but rather about providing the client with a lawyer of their choice. This rationale dismisses the right of a person to have the legal representation they feel is best suited to their case. The Council’s argument undermines not only Besigye’s right to choose but also the principles of justice and fairness.

4. Political Undertones

The Law Council expressed concerns about the political nature of the case, suggesting that Karua’s involvement was motivated by politics, given her association with Besigye and her public stance as an advocate for democracy and human rights.

My View: This is where I find the decision most troubling. The role of the Law Council is not to pass judgment on the political affiliations of individuals involved in legal proceedings but to ensure that justice is served. Karua’s political opinions or affiliations should have no bearing on the decision to allow her to practice temporarily. The Council’s decision seems to be a veiled attempt to politically sideline a lawyer based on her association with a political opponent of the government. This kind of interference in legal matters not only compromises the integrity of the Law Council but also undermines the fairness of the trial itself.

5. Conduct Before Approval

Karua was accused of “holding out” as an advocate before her application had been approved, due to her presence at the court proceedings.

My View: Karua made it clear that she was attending the proceedings as a visiting jurist awaiting approval. She did not mislead the court or claim to be practicing without a license. The accusation seems to be an exaggeration, designed to discredit her professional integrity. This accusation, made without substantiation, adds to the sense that the Law Council was looking for any excuse to deny her application.

6. Logistical Constraints of the Law Council

The Law Council mentioned that it could not expedite the application process due to its members’ full-time commitments in other roles, making it difficult to process Karua’s application on time.

My View: This is a failure of institutional management rather than a valid reason to deny an application. If the Law Council is unable to manage the process in a timely manner, it speaks to the need for reform within the institution. A delay caused by the Council’s own logistical constraints should not serve as a reason to deny an individual the right to practice law in Uganda, especially in a case of such significance.

—

The Double Standards of the Law Council

One of the most glaring inconsistencies in this case is the selective application of the Law Council’s rules regarding foreign lawyers. Historical precedents show that the Council has granted temporary licenses to foreign lawyers when it suits the political interests of the government. For instance:

John Khaminwa, a Kenyan lawyer, was allowed to represent President Museveni in a high-profile election petition before the Ugandan Supreme Court in 2001.

Jim Gash, an American lawyer, was granted a temporary license to represent a client in Uganda, working on juvenile justice reform.

These instances clearly demonstrate that the Law Council is capable of granting temporary licenses to foreign lawyers when it is politically convenient. However, when it comes to a case involving a prominent opposition figure like Dr. Besigye, the same flexibility is not applied. This selective approach casts doubt on the impartiality of the Law Council and raises questions about whether political considerations played a role in the denial of Karua’s application.

—

The Regional and International Implications

The refusal to grant Karua a temporary practicing license also raises important questions about Uganda’s commitment to regional integration. The East African Community (EAC) Treaty and its protocols, including the Mutual Recognition Agreement (MRA), emphasize the free movement of professionals across member states, including legal practitioners. By denying Karua’s application, Uganda is in direct contradiction of these commitments, which could harm the spirit of regional cooperation that the EAC seeks to foster.

Uganda’s actions appear to undermine the EAC’s goal of facilitating the free movement of labor and professional services. This decision is particularly paradoxical given President Museveni’s strong advocacy for regional integration. If Uganda continues to place political barriers in the way of legal professionals from other EAC member states, it risks isolating itself from the very integration processes that Museveni has long championed.

—

The Uganda Law Society’s Advocacy for Reform

In response to the Law Council’s decision, the Uganda Law Society (ULS) has rightly condemned the denial of Karua’s application as per incuriam—legally flawed. The ULS has also called for reforms to ensure that such decisions are made impartially, without political interference. Some members of the ULS have even gone so far as to advocate for the abolition of the Law Council altogether, citing its growing susceptibility to political pressure and inefficiency in handling applications for foreign lawyers.

I fully support this call for reform. The Law Council, and indeed all legal institutions, must operate with full independence, free from political influence. The integrity of Uganda’s legal system depends on the ability of lawyers to perform their duties without fear of political repercussions. The Law Council’s decision in Karua’s case demonstrates the need for urgent reform to ensure that legal institutions are better equipped to serve the principles of justice impartially.

—

My Call for Reform and Conclusion

In conclusion, the Uganda Law Council’s decision to deny Martha Karua a temporary practicing license is not just a legal misstep but also a reflection of broader issues within Uganda’s legal system. The refusal to grant the license based on procedural technicalities, political undertones, and double standards casts doubt on the impartiality and fairness of the decision-making process. Furthermore, it contradicts Uganda’s commitments to regional integration and the free movement of professionals within the East African Community

About author:

The author is a Rule of Law enthusiast working at M/S Okurut-Magara Associated Advocates in the up country Town of Adjumani.

DISCLAIMER: all information in this blog is for general knowledge and educational purposes and is not intended to provide legal advice. Readers are encouraged to seek qualified attorneys in their areas of Jurisdiction for situation specific legal advice and courses of action.

Contact us:

Mobile, 0789856805

ambrosenen@gmail.com.