Uganda’s judiciary stands at a defining moment. With its recent pattern of issuing injunctions against the Uganda Law Society’s (ULS) internal processes, the courts appear to have placed themselves in opposition to democratization, accountability, and reform. The High Court’s recent ruling in Mugisha Hashim Mugisha & Pheona Nabasa Wall v. ULS, which blocked an Extraordinary General Meeting (EGM) to elect ULS nominees for the Judicial Service Commission (JSC), is the latest episode in this disturbing trend.

But this isn’t just about one ruling. It’s about a systemic pattern: one where the judiciary blocks ULS EGMs for years, grants temporary injunctions that morph into indefinite barriers, and delays rulings while the status quo prevails. Cases such as Brian Kirima v. ULS (2024) and Attorney General v. ULS (2024) illustrate this concerning dynamic, where judicial delays and contradictory rulings obstruct the ULS’s statutory mandate to protect the rule of law.

The question we must ask is simple but urgent: Is the judiciary afraid of the Radical Surgery being performed by the Radical New Bar? Is this an attempt to resist reform and entrench unelected power in Uganda’s legal system?

The Radical New Bar’s Vision for Reform

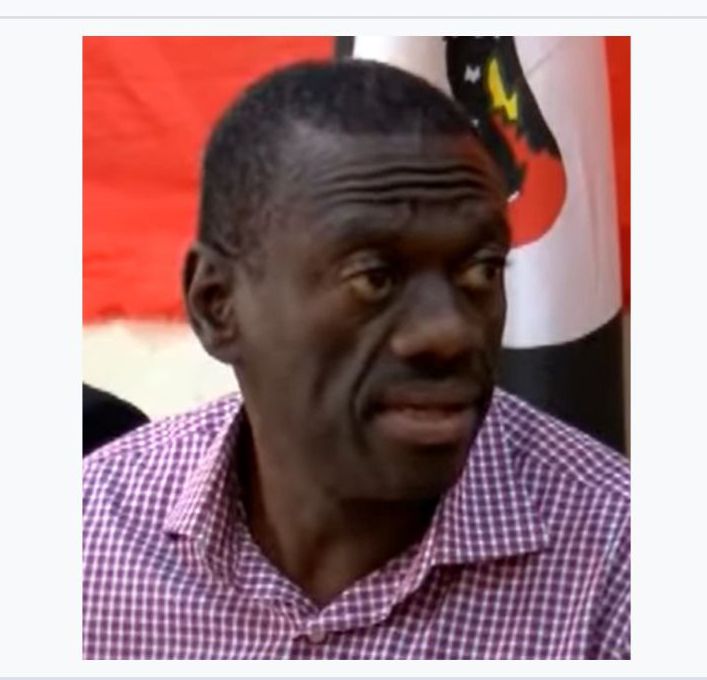

Under President Ssemakade, the Radical New Bar has spearheaded a bold revolution. This movement is more than a change in leadership—it’s a demand for transparency, democracy, and accountability across Uganda’s legal system. The adoption of Executive Order No. 2 of 2024 was a defining moment, directing the ULS to convene elections for JSC nominees. These elections represented a critical step in dismantling decades of unelected power and reforming the judiciary.

For too long, unelected ULS representatives have served on the JSC well past their lawful tenure. These representatives wield significant power over judicial appointments, often without public accountability. Ssemakade’s reforms sought to change this by ensuring that ULS members could elect their representatives democratically—a step toward restoring public trust in the judiciary.

But the judiciary’s recent rulings raise a troubling question: Are the courts complicit in protecting the unelected elite and resisting much-needed reform?

Judicial Overreach: A Pattern of Obstruction

The recent ruling in Mugisha & Wall is part of a broader pattern of judicial interference. Courts have repeatedly issued injunctions that block the ULS from convening EGMs, leaving important governance issues unresolved. In Brian Kirima v. ULS (2024), for example, the High Court issued a temporary injunction blocking the ULS from holding an EGM requested by its members. The court justified this decision by claiming that the meeting might lead to resolutions outside the ULS’s statutory mandate.

Similarly, in Attorney General v. ULS (2024), the court issued a permanent injunction prohibiting the ULS from convening an EGM to discuss judicial misconduct allegations. The court argued that such discussions would infringe on the independence of the judiciary and encroach on the Judicial Service Commission’s (JSC) mandate. While protecting judicial independence is crucial, these rulings have had the effect of stifling the ULS’s role as a watchdog for the rule of law.

The judiciary’s actions create a chilling effect, sending a message that the ULS cannot hold its own members or representatives accountable without judicial interference. This is particularly troubling when unelected JSC representatives continue to serve beyond their lawful tenure, shielded by the very courts that should ensure accountability.

Preliminary Issues Ignored: A Missed Opportunity

The Mugisha & Wall case could have been resolved on preliminary issues, sparing the judiciary from issuing an injunction that has paralyzed ULS processes.

1. The Question of Locus Standi

The first applicant, Mugisha Hashim Mugisha, lacked the locus standi required to bring the case. Judicial review, as outlined in Rule 3 of the Judicature (Judicial Review) Rules, 2019, is reserved for those who can demonstrate that they are directly affected by an administrative decision. Mugisha was neither a candidate for the JSC election nor a suspended council member. His application, therefore, lacked the specific and tangible interest necessary for judicial review.

This procedural flaw should have been addressed as a preliminary issue, as it rendered the entire case speculative and unwarranted. Resolving this question at the outset would have saved valuable judicial resources and avoided the need for an injunction that undermines democratic processes.

2. Wall’s Ineligibility for the JSC

The second applicant, Pheona Nabasa Wall, was constitutionally disqualified from being nominated to the JSC. Article 146(2)(b) of the Constitution requires nominees to have 15 years of standing as an advocate of the High Court. Wall’s candidacy was contested by the ULS Elections Committee, which submitted an affidavit from Brownie Ebal stating that Wall had only 14.6 years of standing as of December 3, 2024.

This affidavit, a critical piece of evidence, was never challenged or controverted by Wall. Under Ugandan case law, uncontroverted evidence is deemed admitted. In Samwiri Massa v. Rose Achieng (1978), the Court of Appeal held that failure to rebut sworn evidence amounts to acceptance of its truth. By failing to address this disqualification as a preliminary matter, the court allowed a constitutionally flawed case to proceed.

Had the court addressed either of these issues, the Mugisha & Wall case could have been resolved early, preserving the judiciary’s resources and ensuring compliance with constitutional and procedural law.

Delayed Justice: A Crisis of Accountability

Another critical issue raised by this ruling is the delayed justice that has plagued Uganda’s legal system for years. The Mugisha & Wall case is not unique—temporary injunctions like those in Brian Kirima v. ULS have effectively frozen the ULS’s ability to act for years. The main cases often remain unresolved, leaving the temporary orders in place indefinitely.

For instance:

In Brian Kirima v. ULS (2024), the court blocked an EGM requisitioned by ULS members, claiming it might lead to illegal resolutions. However, the main case remains unresolved, and the temporary injunction continues to prevent the ULS from fulfilling its statutory mandate.

In Attorney General v. ULS (2024), the court ruled against an EGM to discuss judicial misconduct, citing concerns over judicial independence. This ruling has effectively shielded unelected representatives and delayed meaningful conversations about reform within the ULS.

Such delays raise serious concerns about the judiciary’s commitment to justice. Is the judiciary using procedural delays to block reform and protect entrenched interests?

The Unelected JSC Representatives: A Block on Reform

The judiciary’s rulings have effectively protected unelected ULS representatives on the JSC, who continue to serve beyond their tenure. These representatives hold immense power over judicial appointments, shaping the judiciary in ways that lack public accountability. Ssemakade’s Radical New Bar sought to challenge this system by introducing elections for JSC nominees, but the judiciary’s actions have delayed this critical reform.

Without elections, the same unelected representatives will continue to serve well past February 2025, when their lawful tenure expires. This delay not only undermines democracy but also perpetuates a system where judicial appointments remain opaque and unaccountable.

Benedicto Kiwanuka’s Warning: A Judiciary at Risk

The story of Benedicto Kiwanuka serves as a grim reminder of what happens when the judiciary fails to uphold the rule of law. Kiwanuka’s abduction and disappearance under Idi Amin’s regime marked the judiciary’s collapse into irrelevance. His fate was not just a personal tragedy but a warning about the dangers of judicial complacency.

Today, the judiciary risks repeating this history. By obstructing reform and delaying justice, the courts are eroding public trust and undermining their own legitimacy. The Radical New Bar recognizes this danger and is committed to ensuring that the judiciary remains a pillar of democracy, not a shield for entrenched interests.

A Call to Action: Defend the Rule of Law

To the judiciary, we issue this warning: The Radical Surgery cannot be stopped. Reform is coming, and the judiciary must choose whether to lead the way or be swept aside. The courts must stop obstructing ULS EGMs, resolve cases without delay, and uphold their own precedents.

To the ULS, we say this: Continue the fight. Defend your autonomy. Resist judicial interference. The Radical New Bar stands with you.

Conclusion: A Revolution Awaits

The judiciary is at a crossroads. It can choose to embrace reform, uphold accountability, and restore public trust, or it can continue to obstruct progress and protect the status quo. The Radical New Bar will not falter. We will fight for transparency, democracy, and justice at every turn.

This is not just a reflection—it is a revolution.

Disclaimer:

These reflections are informed by Uganda’s legal and historical context. They do not seek to interfere with pending judicial matters but aim to provoke meaningful dialogue about the rule of law in Uganda.