🪶 The Fable

Deep within the Mambo Forest, the animal kingdom lived in awe of a single, dazzling truth: their ruler, Twon Gweno the cock, wore a crown of living fire. His comb was a legend, a crest of such vibrant crimson that the elders swore it was a fragment of the first sun. His morning crow was a decree:

“Bow to my glory, and you will be spared my flame.”

And so, the animals bowed. Fear made them pious; fear made the cock sovereign with unquestioned loyalty, respect and cooperation from the rest of the animal kingdom in that forest. It was a classic case of natural-born legitimacy; never really earned.

One evening, a crisis struck. Ichuli, the fox, the sole specialist in lighting the communal fire, was away. The wood was piled, but the spark was missing. The night, cold and predatory, loomed.

Odyek Odyek, the hyena, a friend to truth and enemy of pretence, stepped forward.

“The solution is simple,” she said. “We bow to Ladit Twon Gweno’s crown of fire. I will sprint to his home and borrow a spark.”

She took a tuft of the driest spear grass, the Obia and went to the cock’s compound. She found him in a deep, unconscious slumber. Without waking him, she gently pressed the grass to his legendary crown, waiting for the catch, the sizzle, the proof.

The grass rested on the crown, as inert as if it had been placed on a cool stone. The legendary fire was a phantom.

Odyek Odyek, the hyena returned to the gathering and dropped the cold, unburnt grass in the centre of the circle. No words were needed. The lie they had bowed to for generations unravelled in that silent moment.

Power, and unearned but coerced legitimacy unmasked, bled its authority into the silent night.

⚖️ The Lesson

Borrowed fire must warm the hearts of the people. When it no longer does, the borrower is called to account.

So it is with the courts. The robe, the gavel, the summons, and the warrant are instruments loaned by the people. Article 126(1) of the Constitution does not sing an ornament; it issues a command:

Judicial power is derived from the people and shall be exercised by the Courts in their name and in accordance with the law and their values, norms, and aspirations.

🧱 The Three Pillars of Legitimacy

Legitimacy; the respect of the people and their cooperation with the courts, is the covenant at the heart of that loan. It demands three sacramental elements:

Reflection: Judicial power must reflect the values and aspirations of the people; not the insatiable appetite of a sophisticated elite for luxury or high life.

Truth: Courts must administer justice in accordance with law and truth, not convenience or midnight deals.

The Judicial Oath: The solemn undertaking before God to do justice to all manner of people without fear, favour, ill will or affection is no actor’s prayer; it is a chain of duty.

Strip away any of these, and what remains is a gowned pretender, eloquent and majestic, perhaps, but hollow: a cock whose crown no longer burns.

The Evidence of Decay

For those who have seen:

• Appeal files missing thirty-eight pages.

• A High Court hearing conducted not in a public courtroom but secretly in a posh hotel in which 15 minutes out of those proceedings were conducted in the absence of the opposite party and the whole process bashed by the Court of Appeal for want of a fair hearing and lack of judicial accountability and transparency and thereby further exacerbating the already slim public trust in the Court system entirely

• A lower bench judicial officer bashed; “I don’t want to see this rubbish here, take it back where it came from” when they had sought guidance over files of thousands of remand detainees who had clocked mandatory bail, over 5 years where the Office of the Director of Public Prosecution state attorneys appeared neither willing nor ready to commit them for trial in the High Court.

• The poorest peasants completely blocked from accessing justice because the lower courts have received directives not to register and dispose of customary land disputes unless a surveyor had first rendered a preliminary survey report; peasants who have never heard of, met heard about or hired the services of a professional called a surveyor. They have to sell a chunk of land to afford a surveyor to conduct a preliminary survey and get their case registered.

• A National Bar Association President’s liberty preserving Application for stay of execution of a manifestly void Contempt of Court ruling take close to 9 months without disposal.

These are not footnotes; they are flesh-and-blood indictments.

The 1995 Constitution’s promise of a speedy and fair hearing has become hot air—Kikwangala, Kichupuli, Kawani.

🗣️ The Test — The Philosophy of Insults. Withdrawing legitimacy and requiring that it be earned back by fidelity to its 3 pillars.

“To insult without malice but with evidence is to perform constitutional maintenance and maintain pure legitimacy.”

Hence the philosophy of insults. This is not the petty malice of a tavern quarrel. It is a civic stress-test, a pressure gauge for legitimacy.

It is the public’s cry:

“GIVE US WHAT YOU OWE US.”

We lent you power; we demand accountability in return.

A people that cannot insult and mock power has already lost moral authority. The right to insult and offend the powerful is not a luxury, it is the citizen’s tool for testing whether the borrowed flame is real.

📜 The Proof — The Jurisprudence of Defiance

“Leaders should grow hard skins to bear.”

“Power must endure insult to remain clean.”

Uganda: When the Constitution Answered Back

This philosophy is not just wisdom; it is the settled weight of law. Consider Andrew Mwenda, whose words rattled the Republic:

This philosophy is not just wisdom; it is the settled weight of law. Consider Andrew Mwenda, whose words rattled the Republic:

“You see these African Presidents. This man went to University, why can’t he

behave like an educated person? Why does he behave like a villager?’

Museveni can never intimidate me. He can only intimidate himself ……… the

President is becoming more of a coward and every day importing cars that are

armor plated and bullet proof and you know moving in tanks and mambas, you

know hiding with a mountain of soldiers surrounding him, he thinks that, that

is security. That is not security. That is cowardice”

Actually Museveni’s days are numbered if he goes on a collision course with

me.”

You mismanaged Garang’s Security. Are you saying it is Monitor that caused

the death of Garang or it is your own mismanagement? Garang’s security was

put in danger by our own Government putting him first of all on a junk

helicopter, second at night, third passing through Imatong Hills where Kony

is ?……Are you aware that your Government killed Garang?”

I can never withdraw it. Police call them, I would say the Government of

Uganda, out of incompetence led to or caused the death of Garang”

When the state reached for iron law and charged him with sedition, the Constitutional Court answered with freedom, declaring that people from all backgrounds enjoy equal rights of expression, polite or not.

“……Our people express their thoughts differently depending on the environment of their birth, upbringing and education.

While a child brought up in an elite and God fearing society may know how to address an elder or leader politely, his counterpart brought up in a slum environment may make annoying and impolite comments, honestly believing that, that is how to express him/herself.

All these different categories of people in our society enjoy equal rights under the Constitution and the law. And they have equal political power of one vote each.Then came the killer line that buried sedition:

“……During elections voters make very annoying and character assassinating remarks and yet in most cases false, and yet no prosecutions are preferred against them. The reason is because they have a right to criticize their leaders rightly or wrongly. The Court concluded “Leaders should grow hard skins to bear.”

A copy of the judgment can be found here:

Burkina Faso: The Continental Echo

In Burkina Faso, journalist Issa Konaté was jailed for calling a prosecutor “a criminal in a robe.” In his Words:

“…….The Prosecutor of Faso is the godfather of bandits. He is the sponsor, the organizer, the leader of a vast network of counterfeiters and traffickers that he protects with his power and status.”

This is a prosecutor who does not prosecute crime, he commands it. He is not a guardian of order but a godfather of disorder

While honest citizens sleep in fear, the chief lawman of our nation sits in his office, dividing the spoils of crime with police officers and bankers

He is not a magistrate; he is a criminal in a robe. A saboteur of justice…….”

The African Court answered with thunder and reason. Custodial sentences for speech are a bludgeon against Democracy:

“The Court is of the view that the violations of laws of freedom of speech and the press cannot be sanctioned by custodial sentences, without going contrary to the provisions of Articles 9 and 19 of the Charter”

The Court pronounced itself on the role of public figures under scrutiny.

“There is no doubt that a prosecutor is a public figure; as such he is more exposed than an ordinary individual and is subject to many and more severe criticisms. Given that, a higher degree of tolerance is expected of him”

A copy of the judgment can be found here:

From this we learn that “Power must endure insult to remain clean.”

🪶 The Heritage; The Lango Grammar of Reproof

This civic logic is not foreign to us. In Lango, the sharp tongue has long done the work of reform.

• “Ole yin ibedo dako dako”; “…..you man, you behave womanly…”. It is not cruelty. It is shock therapy for duty and clarion call for the family patriarch to “man up” and live up to his responsibilities to his family, to lead firmly, provide for it and protect it.

• “Lango mito alek”; “…..Lango deserves a pestle…” A reminder that discipline is coming unless reform comes first and that it intact comes usually after enforced discipline.

• “Kwany Ka Point” The Gen Z’s and Millenials have similarly curved their own wisdom, “pick only the point”: As plain and simple as that. Pick only the point, filter it from the insult.

• “Ikok Ugali idogi.” “…..You will cry with Ugali in your mouth. …”

In the old rite of passage, a young man’s two upper incisors were pulled, and boiling herbal Ugali was placed in his mouth to ease the agony. He cried through the very remedy meant to heal. Reform rarely feels like mercy.

So when the citizen mocks the powerful, the intention is not cruelty; it is Ugali in the mouth of power: a necessary sting, a painful antidote.

The insult becomes a civic anaesthetic; searing, brutally humiliating, but designed to cleanse and restore legitimacy

Reform rarely feels like mercy.

So when the citizen insults and mocks the powerful, the intention is not cruelty. It is Ugali in the mouth of power: a necessary sting, a painful antidote.

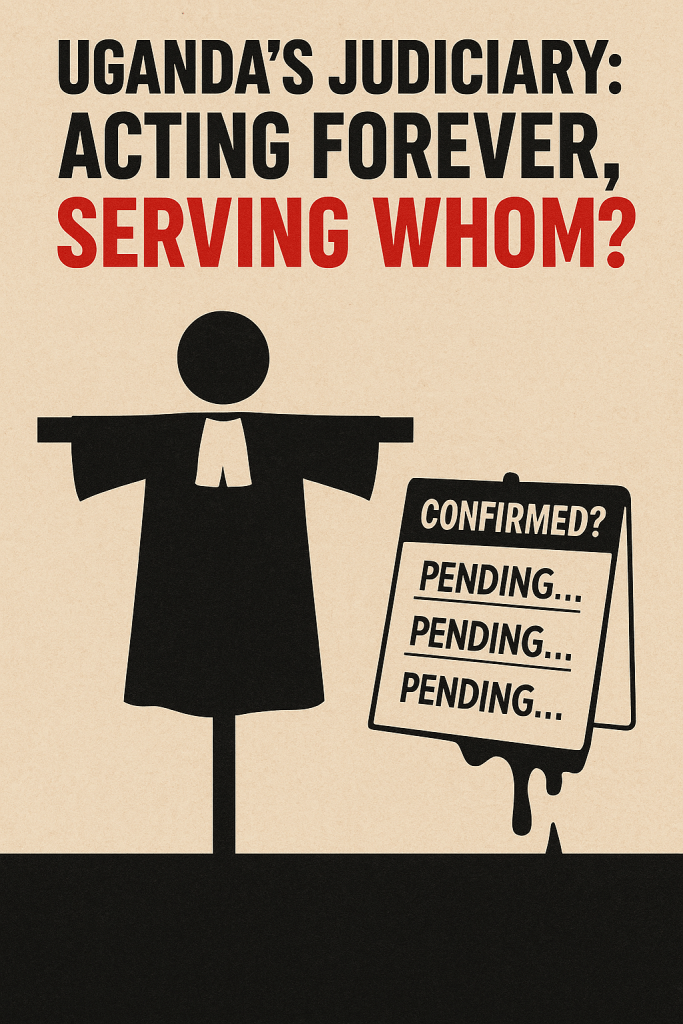

🔥 The Repair — The Calculus of Force

Public outrage, properly aimed, creates four fields of pressure that make corruption intolerable:

1. Professional Ostracization: When integrity collapses, the social scaffolding of a career falls with it.

2. Erosion of Authority: A judge who loses public confidence loses jurisdictional muscle and may in fact receive fewer to zero allocations of files to handle or minimal chances to be chosen to sit on a panel in the case of hearings in courts that are manned by more than one Judicial Officer.

3. Legal and Institutional Siege: Scandal catalyses petitions, litigation, and oversight that eat at illegitimacy.

4. Political Abandonment: The appointing power prefers a scapegoat to a scandal, forcing a “voluntary” exit.

From this, we learn that insults are not instruments of mob rule; they are the social physics of accountability.Yet outrage alone is not reform. The sting must translate into architecture: cooling-off periods for judges, transparent appointments, and independent oversight with teeth. Shame, the direct consequence of insult, reveals the rot; law must excise it.

⚔️ The Awakening — The Price of Truth

“The hyena who taught the village to see.”

For too long, the Uganda Law Society was a sleeping giant while the temple burned. But the dry grass is now burning in Masaka.

When the President of the Bar , the hyena who taught the village to see, lives in exile for refusing to apologise for truth, his banishment becomes the ultimate test.

📜 The Counsel; A Call to the Bench and the People

This is not an invitation to vulgarity for its own sake.

Insult as a civic weapon must be wielded with evidence, not rumour; with satire steeped in fact, not malice.

To the Judges:

Grow the hard skins the Constitutional Court commanded you to have. Wear patience as armour, not menace. Treat insult as a thermometer, not as treason or contempt.

When a citizen insults, ask: does this insult point to truth? If yes, answer in reason, remedy the wrong, and let the nation watch you Act. If not, let the insult fall like a pebble. The dignity and legitimacy of the bench is earned by magnanimity and the stoic creed of the 3 pillars of legitimacy namely Reflection (of law, values, norms and aspirations); Truth and by abiding by the Judicial Oath. It is not enforced by fury, bullying or jaling dissent.

This doctrine requires courage from all sides. The Bar must be relentlessly courageous and fearless in its insult and ridicule while exacting in its ethics.

The public must be loud and literate, hurl insults but bring evidence. Lawyers must translate courage into petitions, not merely WhatsApp gossip and tweets. The Legislature must codify protections for speech against disproportionate criminal sanction and the Judiciary must redicscover the humility of the oath, the most important leg of judicial legitimacy; to do justice without fear, favour, ill will or affection.

To

the citizens: Wield the pen. Make the insult precise devastatingly; threads that link to missing pages, memes that reveal truth.

🌞 The Benediction & Epilogue

Lock and Roseau taught and we learnt from the social contract doctrine that all power, judicial power inclusive, like the communal bull, is never owned. It is loaned to serve, not to feast upon. Judicial officers are, therefore, commissioners, agents of the people, not monarchs. The people are the principal. When the agent betrays, the principal must insult loudly in true reprimand.

If those entrusted with it betray the trust, the people must remind them, sometimes with satire, sometimes with searing words, that borrowed fire must warm, not burn.

This is neither an incitement to violence nor a call for insurrection. It is a call to civil carnage against corruption, ritualised, and peaceful.

Let the insults be sharp, witty, and relentless, and let them dismantle rotten cartels of impunity.

Turn every courtroom cover into a public syllabus: transparent reasons, readable judgments, accountability writ in footnotes and public records.

Make the institutions bleed truth, not people.

To end illiteracy in justice, let every citizen wield the pen.

Let the hyenas come. Let the baraza be noisy.

Let society test the crown every morning until the judges can point, with open hands and clear reasons, and say:

“Here is the flame.”

Until then, press the grass. Let the crown be tried in daylight.

Let the fire prove itself true.

✍️ Dedication

This blog is dedicated to all prisoners, present and past, of conscience, self-expression, and free speech: Male Mabirizi Kiwanuka, Ivan Samuel Sebadduka J, and Isaac K. Ssemakadde (SC), President of the Uganda Law Society, for executing a civic duty tragically confused with contempt of court.

Contempt must be reserved for direct obstruction of justice, not as a cudgel to discipline ridicule.

Imprisoning insult and mockery is to forget the nature and source of judicial power: the people’s consent.

May the Good Lord bless and protect you all.

And may we witness, in our lifetime, thick-skinned judicial officers who treat insults with nothing more than “a wry smile,”

as aptly put twenty-five years ago by the eminent British jurist, Lord Justice Simon Brown.

The author is a member of the inaugural Judiciary Affairs Committee of the Uganda Law Society.

DISCLAIMER: This Blog is not a call for mob justice, chaos or disorder against our beloved holders of judicial power and other public power, it is brutal and defiant reminder that illegitimate conduct leads to a withdrawal of respect from the very owners of the power and attracts criminal and administrative sanctions, some as grave as removal from office. It is also to encourage the clean and disciplined judicial officers to continue upholding the consent of the people for them to administer justice by upholding the stoic pillars of legitimacy first mentioned in this Blog, and that with or without climbing the career ladder, God, the original designer of justice will be the ultimate one to reward their efforts both now and in the afterlife.

This blog is not intended to be used as legal advice, and the author denies liability for use of the contents herein as legal advice. Readers are encouraged to consult a licensed Advocate to give them specialised advice and representation.

For feedbacks and comments: ambrosenen@gmail.com.

References.

For further reading or references. I consulted the following books.

1. Politics as a Vocation (Politik als Beruf) by Max Weber

2. Second Treatise of Government” by John Locke.

3. The Social Contract” (Du contrat social) by Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

4. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance” by James C. Scott.

5. How to Do Things with Words” by J.L. Austin.